Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

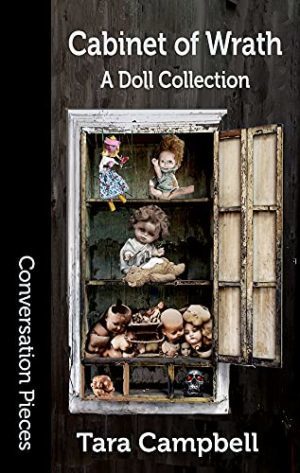

This week, we cover Tara Campbell’s “Spencer,” first published in the March 2020 issue of Speculative City, and now available in Campbell’s Cabinet of Wrath: A Doll Collection. Spoilers ahead!

“I only needed something small from her, something she would barely miss.”

The narrator is unnamed, unless its name is Spencer. Let’s call it Spencer, then. And “it” because it doesn’t mind being considered an object—it respects its roots and doesn’t forget it began life as a novelty ring in a New Orleans shop, a silver skull with faux ruby eyes and tiny silver bones strung into a stretchy circle to fit any finger.

Spencer is sitting with a law officer in an interrogation room. Spencer is quite forthcoming. This whole sticky situation could’ve been avoided if she, the complainant, had just made some effort. She used to think about Spencer and take it out with her most days; Spencer used to make her smile. She even used Spencer as a litmus test for promising men. If they didn’t like Spencer, they weren’t the right ones for her. Why, she found her current boyfriend through Spencer!

Spencer didn’t intend to take much. It started with an index finger. A ring finger would have been more meaningful, but less useful. She made a big fuss over the loss, which was funny, considering how she’d never lifted a finger to put Spencer back together, even though she kept all its bones in a drawer, even though all she needed was a bit of elasticized string.

The index finger proved useless without a thumb to oppose to it, so Spencer took one of hers, the one from her other hand, unfortunately, which was awkward. So it had to take her other thumb, too, no easy task since she slept so little now, preventing it from entering her dreams. Her boyfriend was keeping watch nights, too—ha, not that his observation did any good.

Spencer really meant to stop after taking both her hands, which it needed in order to find more parts and fashion itself a fitting body. It would finger-walk those hands through night alleys, searching for toys. A baby doll was its first vehicle, then a Barbie over whose face its silver skull fit perfectly. Sadly, the doll bodies were all out of proportion to its human hands; anyone who came upon Spencer toddling along was invariably terrified. The officer has probably heard reports about those uncanny manifestations, is perhaps now almost relieved to see their source.

Next Spencer scavenged mannequin parts to make a proper-sized body, using the eye socket of a hollow head to accommodate its “elemental self,” that is, its original skull-ring form. But the mannequin parts were mismatched in size, color, gender. One foot was slightly arched, which gave Spencer a peculiarly tilted gait. It disguised its oddities with long dresses, hats, wigs. Still, people at best wrote it off as a homeless addict and gave it a wide berth. As weeks dragged on, Spencer’s loneliness grew. It was now “something more than a ring on a hand to be ogled, but far less than a being deserving of friendship.”

Buy the Book

The Book Eaters

More flexible joints would help its illusion of humanity, Spencer decided. It began to take more bits of her: a knee, an elbow, a hip. But it wasn’t hard-hearted. It left literature on joint replacement devices. Let them both be “patchwork beings… special, novel, beautifully obscure.” But once again, she wasn’t able to take care of her things. She let herself get life-threatening infections, so wasn’t it more responsible for Spencer to just take the rest of her body?

Spencer supposes the last bit of her is in the station, filing a complaint: “Body stolen from head.” She wouldn’t want to see that body now, though—Spencer’s had to make some “alterations” due to piecemeal acquisition and her own negligence. The officer should let Spencer go before she comes upon it. And—before Spencer decides “to start again, fresh, and do it properly this time, all at once.”

Oh, and may Spencer ask how tall the officer is?

Yes, the officer should let Spencer go right now, but the officer won’t, right?

Pity.

For the officer.

What’s Cyclopean: Fine distinctions can be everything, even in the simplest descriptions. Like the distinction between meant to and did.

The Degenerate Dutch: Spencer doesn’t want to forget its roots as an object, but also wants to be “a being deserving of friendship” in polite society. A body that makes people scream, or tear off its head, or even dismiss its wearer as an addict, are just not sufficient. Nor is a body that’s failing—because its original keeper was undeserving, unwilling to do the work of taking proper care of it. It’s always your fault when your body fails, isn’t it?

Weirdbuilding: How have we not done creepy dolls before? There are creepy dolls everywhere. There could be one in the room with you right now.

Libronomicon: Spencer knows from TV that humans have joint replacement technology, and always leaves “literature on the most dependable devices to replace” what it takes.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The officer talking with Spencer has mixed feelings about what they’re seeing. “Through your revulsion shines a clarity, a relief almost, now that you can see the source of the nightmarish stories.” Though there are… disadvantages… to that clarity.

Anne’s Commentary

When I read that this week’s narrator “began life” as “a novelty ring, giggled over in a shop in New Orleans,” I assumed the shop in question must have been tucked away in some obscure sidestreet. Doubtless it was on the outside a shabby storefront that looked too narrow to contain much in the way of the “Curiosities and Sovereign Cures” its faded signboard advertised; inside, however, it was much more commodious than expected, or even possible, with room for every artifact, nostrum and charm known to the Louisiana Voodoo. Serious practitioners were the shop’s core clientele, but the more adventurous tourist not infrequently sidled inside. For this accidental customer, the shop kept a display case of cheap jewelry and souvenirs. Trinkets for them to purchase when they were overwhelmed by the legitimate merchandise and wanted to make a quick exit minus the possibly dangerous insult of not buying anything.

The shopkeeper might have sometimes placed a more potent item in the tourist case. By mistake, surely. Surely not to teach lessons to snickering tourists: We want to think nothing but good of such a shopkeeper. Or it might have been that the shopkeeper had nothing to do with the birth of our narrator. The atmosphere in obscure shops on obscure New Orleans sidestreets must attract or breed certain presences—certain “elemental selves”—ever alert to slip into the material world, be it only in the lowly form of a novelty ring giggled at by a young woman who’d had one too many a novelty cocktail in a Bourbon Street bar.

Okay, I’ll stop assuming an entire prequel to Tara Campbell’s “Spencer.” In my defense and to Campbell’s credit, she’s crafted a story spare in length but so rich in detail that it invites the reader to riff on what she’s deftly suggested but left unwritten. Or does it compel the reader to riff, perhaps in dream, the place where her narrator works its sinister magic?

I’ll stop again, for real this time. Other considerations aside, I need to admit that I could have assumed too much (and too trope-ily) about the shop where Spencer was acquired. In the summary above, I boldly assumed that the title “Spencer” must refer to the narrator, must be its name. What else could the title refer to? But wherefore is Spencer Spencer, I had to wonder. There are so many other names with more ominous a ring for a cursed ring.

With which I, like Spencer, must add punning to my list of sins. At least I haven’t stolen anyone’s body parts. Hell, even Tutuola’s not-so-gentlemanly skull hires his auxiliary bits and then dutifully returns them to their original owners.

I will dutifully return to the mystery at hand: Why Spencer? Campbell’s description of the narrator’s jewelry form triggered a memory of youthful mall days. It was a novelty ring, so cheaply produced it didn’t even come in sizes but was simply strung together with elastic cord! Something that low-end couldn’t be made of real silver, but of some silver-tone metal that would leave a livid green stain around the wearer’s finger. A real silver skull would deserve at least garnet chips for eyes, not faux rubies. I should know about fake silver and stones, too, because in late grade school and early high school I used to adorn every finger with them, my favorites being the double-headed cobras with fake emeralds for hood markings. These used to break frequently, because the way you made their one-size-fits-all work was that you simply bent the bands to accommodate your chubby digits.

I kept the broken bits in my faux-leather jewelry box. I never fixed them, but they didn’t care. They weren’t ambitious like Campbell’s ring. And I knew exactly where to get more of them, cheap.

Every mall in my area had one of these emporiums stocked with pop culture ephemera, Goth accessories, gag gifts, and sex (aka “adult”) toys. They were temples to the dubiously tasteful, and they were called, as I recall, Spencer Gifts. Or was it just plain Spencer? They do business as Spencer’s now.

So—Spencer came from Spencer’s and took the shop’s name for its own? Or, with characteristic ego, supposed that the shop was named after it? I concede: For the cursed ring to have come from a Spencer’s store is much more ironically delicious than for it to have come from the trope-ical wizard’s boutique I described.

Because Spencer, the ring who became a doll who became a mannequin-human hybrid, and who may now become a human possessed whole in one gulp, is no low-end, faux monster.

Spencer is the genuinely terrifying, yet somehow sympathetic, article.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I have very little patience for stories in which we follow the point of view of a terrible person while waiting impatiently for them to get eaten by a grue (or worse, not get eaten by a grue). And yet, I love stories from the point of view of monsters. What makes the difference?

This question occurs to me now because Spencer—whose story I loved—is definitively not a good person. Not even if we define “person” to include “creepy doll,” which I’m honestly willing to be pretty broad-minded about. He is, in fact, an entitled jerk who would rather destroy a woman and lay claim to her body than experience any inconvenience of his own. And yet, I enjoyed my discomfiting time with him, where my patience with Monty in “Ne Me Impune Lacessit” went into the negative digits at lightspeed.

Maybe it’s because he is a creepy doll, and attitudes that come across as banally evil in humans become interesting from a weirder point of view? I certainly had fun imagining what it would be like to inhabit objects, or combinations of objects, or combinations of objects and body parts—to have one’s very existence depend on the structural soundness and compatibility of those parts. And it’s interesting to think about how much that is, and isn’t, like the experience of depending on the soundness of one body and being stuck in it. If humans could steal bodies that better suited their needs… well, that makes an uncomfortable story too.

But then again, too-human motivations can undermine any monster. When Cthulhu’s interests line up with the worldly temptations of cult leaders, I tend to roll my eyes.

Maybe it’s because of the particular flavor of entitlement, and its mirror-image guilt, that Campbell evokes. I heard this story at a reading in which we were both participants—where Campbell mentioned that she did in fact purchase a cheap tourist skeleton ring, and it did break, and she did stick it in a drawer and entirely fail to get around to fixing it. In fact, while failing to get around to fixing it, she wrote this story, and then continued to leave the ring in the drawer. Campbell is perhaps a braver person than I.

Our lives are so very full of objects. Our lives are so very full of breakable objects, broken objects, objects that straddle the line between instant-fix irreplaceability and the recycle bin. Objects that we swear are worth that dab of glue or replacement battery, next time we have a few minutes free.

Objects to which we have unfulfilled obligations. It’s a good thing they can’t complain, isn’t it? It’s a good thing that they aren’t actually aware of our neglect, that it doesn’t really matter to them how long they’ve waited for our sparse attention.

Monsters are interesting because they get at our fears from new directions. They may have something in common with the banally human bad guy, but their experience of the world is a little skewed—and because of that, they skew our experience of the world. A man who thinks he has rights over my body is frightening, but all-too-mundanely familiar. I need to fight him; I’m not going to enjoy reading about him. An object, on the other hand—an obligation that I’m used to being able to ignore…

Excuse me a minute. I’m just gonna go check my junk drawer, and see if anything needs Superglue.

Next week, we continue N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 6: The Thing in Mrs. Yu’s Pool, and the third Interruption. We’re expecting tentacles.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

This is the scariest friggin’ thing I’ve read in YEARS. Oh my goodness. This is like that Theodore Sturgeon story about the guy who “sees things in a different way,” with the backwards voodoo dolls. But better! Oh my goodness!

Aaaaa, aaaaa, I can just see Spencer skittering around on humanish hands, like the birdhands from Garry Kilworth’s Hogfoot Right and Birdhands, but ~worse~ and ~malevolent~ and… aaaaa!

Excuse me while I frantically click over to bookshop and buy Cabinet of Wrath. Thank you for the recommendation!

I love that this brilliantly powerful and woefully entitled entity came from a Spencers Gifts. I knew there was something else going on with that place – though I also think I still have a few objects (fragments?) from there rattling around (at least, I hope they’re not rattling!) And it’s horrifying to think what must be sitting in that interrogation room… And does it actually think that the head of the woman is in the other room making a report? Does it not understand death? Or is it’s yearning for human connection hiding a deeply cruel sense of humor?

@@@@@ 2. Matt Sanders, have you ever read Theodore Sturgeon’s IT? It’s probably what gave the original cartoonists the idea for Swamp Thing. Sturgeon’s IT has the mind of a baby: completely curious and completely absent of sympathy. But it’s stronger than a human being. Imagine that! The damage a baby could do if it were that strong.

Spencer reminds me a little bit of IT, in that he’s got this tremendous power along with an ignorance of stuff that doesn’t affect him directly. Maybe he doesn’t know what physical pain is! Maybe he can’t imagine that humans have senses or priorities that he doesn’t have.

For what it’s worth, I’ve always imagined my castoff trinkets to be cheering me on in their drawers rather than sleeplessly resenting me. Whenever I come across one, it always makes me feel good and I’m glad I still have it in my home. It’s still part of my history, and a lot of my trinkets I keep in nice boxes. So that makes me think Spencer is a little, like, conceited. Maybe by the time he threatens the cop at the end, he’s starting to learn that he’s got powers other living things don’t have. That could lead to him being malicious, but I don’t think he’s got the capacity for malice through most of the story.